On Thursday, June 5, the Guilford County Board of Commissioners held a public hearing on the proposed 2025-2026 county budget, and over 30 speakers came forward – many of them educators, parents, and school employees – strongly urging the board to increase local funding for the Guilford County Schools system.

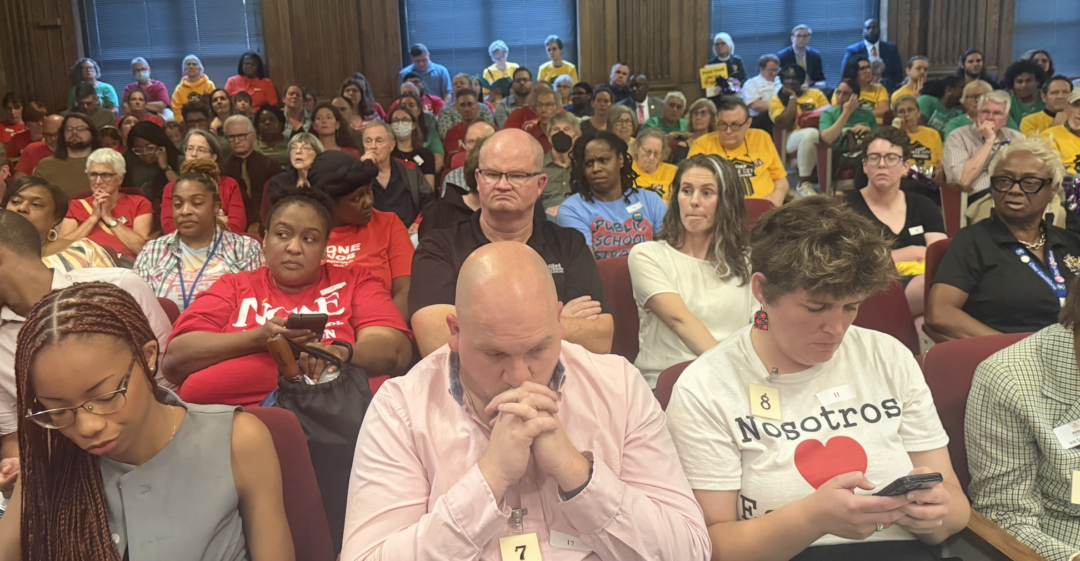

The commissioners’ meeting room on the second floor of the Old Guilford County Court House in downtown Greensboro was packed, which meant many attendees had to view the meeting from the rarely used balcony seating.

The difference between what the school system asked the Board of Commissioners for and what’s in the manager’s recommended budget is vast; however, the board is very school friendly – it includes a current teacher and two former school board members who all like getting money to the schools.

Some other issues came up as well – like a plea for more money to help the homeless and prevent evictions – however, interestingly, not a single speaker at the public hearing asked the board for a reduction in property taxes.

After the hearing, the commissioners thanked the speakers for their input. The commissioners will no doubt try and find some additional money for the schools – they always do – but this year it will be tougher than ever. The county has taken its savings account below levels considered financially responsible by state oversight officials, and the county is also facing a payback of school bond debt of over $3 billion when interest is added in.

The hearing, part of the county’s annual budget process, gave residents an opportunity to speak directly to commissioners about how their tax dollars should be allocated. While the county budget encompasses everything from law enforcement to parks and libraries, the overwhelming focus of public comment was public education.

The first speaker, David Coates, pointed to the amount requested by the school system and emphasized that, in his view, the county had the financial capacity to provide millions more. He referenced a projected surplus and additional expected revenue from next year’s property revaluation as reasons the board should consider going beyond the county manager’s current recommendation.

“Be good stewards of our county’s first and best investment – our children,” Coates said, urging commissioners to recognize the broader economic and cultural strengths of Guilford County and to match them with a strong commitment to education funding.

A high school math teacher named Samantha told the commissioners that she’d chosen her profession out of a love for learning and teaching –a passion that had been instilled in her by her mother, who had also worked in education. However, she described how inadequate pay and declining morale were driving teachers out of the profession.

“Right now, we are facing a budget that will impact students and workers directly,” she said. “We are fighting for every penny possible because we know what it means for our students.”

Another speaker, Brian Carter, painted a picture of schools trying to keep students engaged in the face of resource constraints. He described how weather-related closures had forced schools to rely on virtual learning days. He also said he and other parents were taking their concerns not only to county leaders but also to members of Congress.

“We are running out of options,” Carter said. “If you guys can’t step up and do it, I’m not quite sure who’s left.”

A young mother who teaches and works in a diner told the commissioners that one of her co-workers – Megan – was also a full-time high school teacher who had to work at the diner three nights a week to make ends meet.

“One job ought to be enough,” she said. “Because it’s not, students are suffering. We’re seeing decreases in literacy and other performance issues. Our kids deserve better.”

Sarah Jones, a longtime public school teacher, went a step further. “Please raise my taxes,” she said bluntly. “Send our children to wonderful public schools where they are educated by teachers like me.”

Jones said that after years of infrastructure investment in Guilford County Schools, the time had come to invest in the people.

“We are struggling to bring in new educators who want to work for the amount of money they’ll make,” she said. “This Commission finds itself in a stopgap—but educators understand the circle. We live it every day.”

A Whitsett man told commissioners that, while the county wasn’t solely responsible for school funding shortfalls, it still had a duty to act.

“No matter how inconvenient it may be, these are still Guilford County schools,” he said. He took issue with the idea of preserving savings for a ‘rainy day,’ arguing that the underfunding of schools was already an emergency. “Just because an emergency is ongoing doesn’t mean it stops being an emergency.”

A seventh-grade science teacher addressed not only teacher pay but also the low wages of classified staff – that is, those such as bus drivers, cafeteria workers and custodians.

She pointed out that under the current state salary schedule, teachers with more than a decade of experience have seen little or no pay increases across multiple years.

“We cannot allow our children to pay the price for this funding shortfall,” she said. “Our kids deserve better.”

One speaker, who works in the maintenance department for Guilford County Schools, said that despite his long tenure he and other classified workers often have to take second jobs just to make ends meet.

“We work hard every day,” he said. “We just want to be paid fairly for what we do.”

One teacher who had just received her students’ test scores said she was proud of her students’ growth but disheartened by what she called a lack of recognition from policymakers.

“I am one of those effective teachers,” she said. “But I’m embarrassed – not proud – to be a teacher, because of how little value is placed on our work.”

An 11-year school employee addressed the commissioners with the following question: “What is your why?”

She asked board members to think deeply about the reasons they got into public service and to let those motivations guide their budget decisions.

“This budget is your opportunity to shape the impact you have on people’s lives,” she said at the meeting. “Do all that you are able to provide our public school students the sound education that is their right.”

Another mother with two children in the school system told the commissioners that teachers and school staff are being priced out of the communities that they serve.

“They’re not asking for luxury,” she said. “They’re asking for dignity—a living wage.”

She argued that better compensation for educators would benefit not just students, but also families, neighborhoods, and the broader local economy.

“Raises lift up entire families and strengthen the very fabric of this county,” she added.

One man spoke of education as a long-term investment that builds strength across generations. He told the board that the teachers who changed his life – some of whom had since left the profession – had done so in part because of budgetary choices.

“The kids you’re helping probably won’t remember the numbers,” he told the board. “But they will remember the teachers who supported them.”

One of the final speakers, a mother of two daughters, said the proposed budget left a “deficit in safety, support, and stability.”

She said employees were already stretched thin and morale was low.

“Our children deserve adults who are present, stable, and supportive,” she said. “Not underpaid and burned out.”

The hearing was one of the last chances for people to weigh in publicly on the budget before the budget is finalized later this month. The Board of Commissioners is expected to decide on the fiscal 2025-2026 budget by the end of June.

If money was the answer we should be turning out geniuses. Our current system of education is broken. As Waylon Jennings sang “maybe it’s time to get back to the basics of life “

I agree. Education is the most important area we need to fund. However, we need to stick to educating our children in the basics, first: reading writing, math, and civics. We need to hire certified teachers with a strong background in classroom management. They should be paid appropriately. DEI and CRT needs to be taken out of the curriculum. Schools need to be soundly made and appropriately structured for learning, keeping in mind this is public money. Construction should be fiscally responsible, ie no major open space to add to heating/ac expenses, no elaborate $$ structures.

Scott, I have cried in my beer and choked when I read one teacher said to raise her taxes. I suggest to all those begging for more school funds to look at the waste in the school structure and start cutting out their waste. These people had the chance to also tell the commissioners to stop their waste on personal pet projects etc and other grifters who want a handout. I would hope year end test would improve but I see little to no improvement and the yearly budget school increases don’t seem to make a difference. Based on recent news, seems like Forsyth, Guilford and Alamance school systems have no clue what they are doing other than wanting more millions each year.

I’m not sure where there is waste when the state and federal tell the schools how to use the money. Schools have done the best with what was given. Guilford always has a good audit. There’s no wiggle room. The local requests are the only time schools can request what they need. If you continue underfunding we will continue the cycle of no win scenarios and educators doing their best with what is given.

“…over 30 speakers came forward – many of them educators, parents, and school employees – strongly urging the board to increase local funding for the Guilford County Schools system.”

I’m shocked…SHOCKED to find audience packing going on here!

Thank you. There will be a little something for you later.

How many of us are not surprised the County Commissars packed the meeting with their flunkies?

Cue the Board sycophants wiht their faux outrage.

Dead right, Patrick. The people who are paid by the school system demanding more money… for the school system!

Mandy Rice-Davis Applies.

There have always been thoughts that only parents should pay the school tax. Having no kids I used to agree. Then I began to play and spend time with the kids in the neighborhood. The difference between the home schooled children, tbe Charter School children and the public school children is absolutely amazing to observe. I do not think the State should provide voucher to every single family for charter schools. I think that public schools have fallen behind for a variety of reasons, not just linked to money. My mother taught 30 years in the Greensboro School system during the times of ending segregation. She helped break up fights and teach kids and parents that everyone is equal. She taught everyone that. She spent extra time helping those that needed help the most. She sponsored activities for every kid in the 8th grade at her school. You do not see that in public schools anymore….why? Not that teachers don’t want to but the rules prevent them from doing it. Teachers can’t be teachers anymore. But parents aren’t parents anymore.

Charter Schools are public schools and Governed by NCDPI

I wondered did any of the 30 speakers mention the fact that Guilford County schools is bloated with bureaucracy and is doing a poor job of educating the children having nothing to do with money but poor management. Primary goal of education, reading, writing arithmetic with some American history thrown in, test scores indicate we’re not doing a good job. We should be asking more of our schools before we throw money at them and more from the parents in the area of discipline and engagement.

Not again!!! School employees will ALWAYS want more money, and will ALWAYS say they are underpaid, etc. How many Asst Superintendents, or Deputy Asst Supts, or Asst program managers, and assistants to the assistants do they have or need? Where is Elon Musk when we need him to evaluate the optimum number of employees to run an administration? Having worked in government HR in the past, I can assure you there is “bloat” in any organization, but the occupiers of those bloated organizations will always want more than they need, and that includes elected officials who need the votes and support from the bloated employees. See how this works?

Maybe now is a good time to do an audit. Any employee who directly supervises less than 5 employees should be eliminated. Guess the school system doesn’t understand the optimum employee to supervisor ratios.

Perhaps DOGE should come to Greensboro specifically to audit the Guilford County Schools and their exiguous annual funding upon which they must survive. Maybe then we could plainly see where the money trail leads. I’m thinking we could use several more Assistant Superintendents to relieve those we burden with the task of managing our school system of some of the burden for which we compensate them generously.

I will repeat what I stated at least twice in past comments: The City and County should take the number requested by the school system, add 10% and write the check. In two weeks or less, the system will be back asking for more.

A friend once told me that a boat was a hole in the water that you fill with money.

Why is it that certain private schools, working in facilities considered inadequate, with funding considered likewise inadequate, and teachers without a teaching certificate, are graduating students being sought by universities for their achievements thus far in their educational lives? And don’t give me the BS that these are cherry picked students, because many are not thus selected. I am specifically saying I do not consider credentials to be unimportant, only that is also not the answer.

I absolutely do not claim, herewith, that I am in possession of all the answers. But when I make a purchase at a local shop and observe the young cashier struggling to make change, particularly if there are two or three pennies involved, and I say, here are the pennies, the ensuing catastrophe almost makes my cry.

If we need more educators specialising in subjects such as DEI, rather than a math class, I guess I’m just way too old.

The speakers would qualify as shills. I’m sure they wouldn’t like what I would say. Anyone who asks for more taxes is a fool.

This is why our taxes are so high. People are dumb & ignorant enough to think the more taxes will help everyone, especially those who get freebies and special dispensations from the govt. Govt schools indoctrinate our children. Teach them what to think, not how to think.

You get what you vote for. If you want Libertarian legislators, you have to fund their advocacy, get them on the ballot, and vote for them. Any chance of that happening?

Watch Neil Oliver on social media.

They will soon have no choice when the bloated and wasteful Dept. of Education is closed in Washington. Get in the habit, Commissioners, and stop thinking of ways to spend our money for yourselves!

Maybe we need a DOGE for our school system. Clearly throwing money at GCSS is not working. We tax payers do not have a bottomless pit of tax dollars to keep giving the school system. The people of this county do not want their sales tax’s increased but they vote to increase property taxes as they don’t think they pay those taxes but if they rent their rent goes up because of the increase. I would begin to tag all increases to the physical budget ( not buildings) of GCSS to a sales tax increase going forward. Every person who spends money in the county pays these taxes. You can let our property taxes pay for the 2 BILLION Dollars of bonds the county residents have voted on as this will take an extra 1.2 Billion dollars of interest on top of the 2 Billion bond but if you keep pushing up the property tax rates and values people will leave and live 15 miles down the road. Just look what’s happening to California.

Well if you dumb son of a b****** didn’t pay the school superintendent almost $300,000 a year that would be a start. Not to mention the thousands of illegals that go to the school that shouldn’t be there to begin with.

Here we have it again, the same volunteer army of lobbyists for the county school system that pushed the bonds thru……I do not believe a significant amount of money remains to be had from the current budget year. But, I do believe this is the opening salvo as the county commissioners and the school board begin building a case for not adjusting the county tax rate after the upcoming re-evaluation. I would say that the possibility of the county going “revenue-neutral” after the upcoming re-evaluation is zero.

Also helping pushed to bonds thru were the great majority of registered voters who didn’t bother to show up at the polls.

Use the Republic, or lose it.

If a Guilford County teacher or cafeteria worker or any other employee of the school system is unhappy for any reason, find another job. It seems that most speakers’ complaints are centered around money. Salaries for NC teachers are purportedly to be low compared to what? It would be a useful exercise to compute a teacher’s salary in terms of hourly rate, not annual salary. If the average salary of a NC teacher is $56,600 annually, and a teacher works 40 hours weekly (which is doubtful,) multiply 40 X 46 weeks worked annually (which is doubtful,) equates to $31.00 hourly. A school administration employee with direct access to the figures should calculate the hourly rate. As a perk, consider the paid days away from teaching such as holidays: Thanksgiving, Veterans Day, Christmas and New Year, spring break (formally Easter,) and others not named. How many Guilford teachers and other employees do not live in Guilford County so, therefore, do not pay property taxes? Regardless of teachers’ salaries, school results are dismal. The teachers who are teaching are not achieving results, and it has nothing to do with money. If it is money, then teachers are motivated only by money. The Commissioner who was a teacher and the two Commissioners who are prior school board members, what happened on your watch? Now you follow Alston and Deena Hayes-Greene by throwing money into a problem that money won’t fix. Property owners’ money. No more issuance of bonds until schools’ results improve significantly, no sales tax increase that 75% will be paid by Guilford County residents, not tourists like Alston wants voters to believe.

The organized teachers’ unions like to demand – demand! – that teachers be paid what they’re worth. I agree.

US students consistently rank around 27th in global testing, so our “educators” should have their pay immediately reduced to the 27th best paid in the World.

Fair enough?

Yeah…..but life is not fair. Just stop sending them all that money, nah gonna happen, either. Every dollar extorted from the taxpayer reduces our freedom by that much. Monetary power eminates from the Federal Reserve. You can thank the Wilson administration for that. Govt & Banks can borrow all they want, and that is what they wanted from the start. Meanwhile, your fiat dollar buys less almost by the day.

the EDU $$ is spent on bus gas driver with student time wasted. a recent commenter spent 2 hours every day getting ‘this’ education. motivated ($ etc) students need only EDU materials, tudors & testing. home schooling is evidence of (in)capable homelife ?

the EDU $$ is spent on bus gas driver with student time wasted. a recent commenter spent 2 hours every day getting this ‘education’. motivated ($ etc) students need only EDU materials, tudors & testing. home schooling is evidence of (in)capable homelife ?

———

Maybe I’m old fashioned but I find this nauseating.

Clamoring for more money for yourself and your buddies… “demanding” that they be handed ever more money… shamelessly shilling for fatter paycheques…

Don’t they realise how selfish and repugnant they look? They’re a bunch of spoiled six year olds having a temper tantrum for a bigger allowance.

Hey, if you want more money go get another job. Otherwise shut up and have some shame.

Public demonstrations like this make me want to puke.

EDU suffers when it becomes a SYSTEM ? capable teachers should ‘hang out a shingle’ & profitably compete for students. i would like to get tutoring on the internet & willing to pay for it – answers to specific questions as i read & study.

As a candidate for Greensboro City Council District 4, I want to thank Rhino Times for covering the recent Guilford County budget hearing and highlighting the heartfelt testimony from our educators, parents, and school employees.

Let me first be clear: The City Council does not have jurisdiction over the county budget. School funding decisions fall under the responsibility of the Guilford County Board of Commissioners, not the Greensboro City Council.

That said, I hear the concerns of teachers and support staff loud and clear. Many are working second jobs just to stay afloat, and that’s not acceptable. Our educators deserve respect, and that begins with fair pay and strong support.

But the truth is, this budget situation also reveals deeper issues. The County is struggling under billions in debt from past school bonds, and its savings have dipped to dangerously low levels. We must be honest: no matter how good the intentions are, we cannot fund everything through endless borrowing or raising taxes without consequences for working families and seniors.

As a City Council candidate, my focus is on ensuring that Greensboro is growing responsibly, creating a strong local economy that helps generate the revenue we need to invest in core priorities—public safety, infrastructure, and, yes, supporting education wherever we can through collaboration and community partnerships.

I will bring 45 years of business leadership and common-sense decision-making. And while I won’t be voting on the county’s budget, I will always listen, advocate, and work to build bridges between city and county leaders so that we stop passing the buck and start solving problems.

—

Nicky Smith

Candidate for Greensboro City Council, District 4

District 4, do not vote for Nicky Smith.

Boo-hoo. Lots of folks are working 2nd & 3rd jobs. I was married to a K-5 schoolteacher. Most work very long hours, and put up with the meddling political circus and feather-bedding administrators. They are paid for the school year, not all year. Many have to take summer jobs. Years ago, teachers learned that the education system was being destroyed by running a graduation mill instead of a learning mill. My ex only stayed on, in order to get her 30-year pension.

You know the people of Guilford County are already struggling with higher taxes everybody is feeling money problems and the school system is already taking a huge amount of money so adjust like we are already have to do.

A lot of people no longer have extra money to do repairs on their houses so they leave them in disrepair makes the county look bad.

What’s Missing from the “Give the Schools More Money” Story

Scott Yost’s article omits several critical pieces of information and context that readers need to evaluate the situation in a meaningful way.

1. How Much Money Are We Actually Talking About?

The article never states how much the school system requested, how much the county manager recommended, or what the actual dollar gap is. Are we debating $5 million? $50 million? Percentages or totals would help readers assess the scale of the issue.

2. What Does the School Budget Look Like?

There’s no breakdown of the current Guilford County Schools budget, nor where local dollars fit in alongside state and federal contributions. Readers need to know:

How much is spent per student?

How much is administrative vs. instructional vs. facilities spending?

Has the overall budget grown or shrunk over time?

3. What’s the County’s Full Financial Picture?

While the article mentions the county’s depleted savings and $3 billion in bond debt (including interest), it doesn’t explain:

What the county’s total budget is.

What proportion of it goes to schools now.

What new revenue is expected from the property revaluation, and whether that realistically can or should be tapped.

4. What Accountability Exists for School Spending?

There is no mention of whether past increases in funding have led to improved student outcomes, retention of teachers, or better infrastructure. What mechanisms are in place to ensure the money is used effectively? How does GCS compare with other similar districts in performance per dollar spent?

5. Are There Competing Priorities?

The article states that other issues like homelessness were briefly mentioned but fails to explore trade-offs. What other departments or services would face cuts if more money went to the schools? Are taxpayers being asked to choose between education and, say, public safety or healthcare?

6. Where Is the Broader Public?

All 30+ speakers favored more school funding, but was this representative of the public at large? The article notes “not a single speaker” asked for tax reductions, but was there anyone present from the business community, taxpayer advocacy groups, or residents on fixed incomes who may have different views?

7. What’s the Role of the State?

North Carolina’s school funding formula places significant responsibility on the state. What portion of the district’s funding shortfall is due to state underfunding, and what efforts are being made in Raleigh to address this? Are commissioners being asked to backfill what’s fundamentally a state obligation?

8. What Are the Commissioners Saying?

Aside from a generic note that commissioners are “very school friendly,” there’s no summary of their actual comments, views, or fiscal philosophy. What constraints are they working under? What alternatives or compromises are being considered?

In Summary:

The article captures emotional testimony but falls short of informing readers about the actual budget choices at stake. A well-rounded report would include the size of the funding gap, key fiscal data, competing priorities, evidence of past results, and the perspectives of policymakers. Without that, we’re left with a chorus of advocacy—but no sheet music to understand what it all means.

This was an article about the meeting. If you google “Rhino Times Schools” you can find articles addressing most of the other questions. Also, to answer all those questions in one article would take about 20,000 words.

I wish “Frank Lee speaking” would stop speaking.

Maybe the County should take back the old prison farm property and turn it into a Debtors Prison for those of us property owning taxpayers that have no money left to pay their outrageous taxes and bribe money going to their bought and paid for “non-profit” voting blocks. In fact, doing so would generate jobs for their sycophants.

Look at it this way Board of Commissars, with that confiscated property you’ll have have the 40 acres and a mule to reward your backers (like Roy). It’s a win-win situation for you.

Great idea Alan, that place used to turn a nice profit for the county, the inmates learned a skill and they were guaranteed 3 hots and a cot

Wait the teachers unions contributed to all of the current candidates campaigns except 2…….the union has the others ( all democrats) in their pocket….not a single person spoke on reducing county spending….money will not fix a broken political system

photo is funny . . . . they all look guilty of sumpfin ! we need a system where teachers ‘hang out their shingle’ & parents hire what they can afford & value ? too much of EDU is daycare/sports ? how/why do some of the public/private schools do so well ? is it all about $$ or all about ‘culture’ ?

Scott, just wondering after watching the budget fiasco in Winston-Salem Forsyth County school

system,does GCSS allow take home cars or pay for employees cell phones. I see that’s a couple things WFCS is cutting out to save money m. I’ve called GCSS and asked them but of course I can’t get a direct answer Maybe you can have better luck. What I saw today was, just those two items will save them over a million a year

today’s WSJ: 35 to 40% of the US economy is guvmnt ! what a voting bloc ! who could win election against that ! take a guvmnt job & lose voting rights. fox guards henhouse !