On Sunday, December 7, the Greensboro Parks and Recreation Department will kick off a yearlong celebration at Gillespie Golf Course to honor the “Greensboro Six” – the six Black men whose actions on that date in 1955 helped force the integration of the then whites-only municipal course.

The event begins at 1:30 p.m. at Gillespie, 306 E. Florida St., with a ceremonial tee shot by six individuals to mark the 70th anniversary of what’s now recognized as one of Greensboro’s earliest and most consequential civil-rights moments.

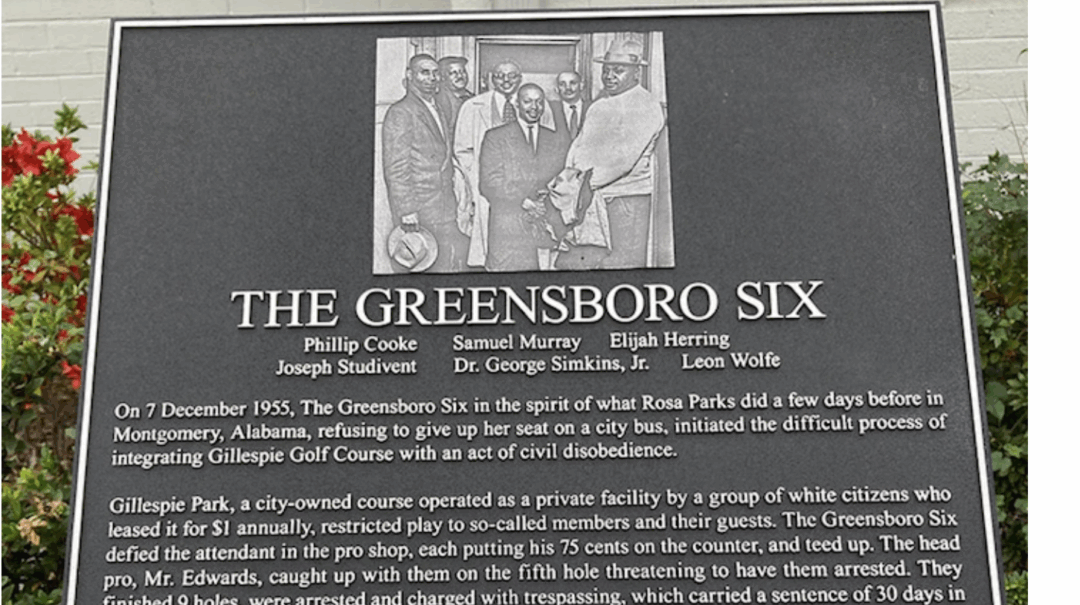

The six men – Dr. George Simkins Jr., Phillip Cook, Elijah Herring, Samuel Murray, Joseph Sturdivant and Leon Wolfe – will be remembered throughout the afternoon, including during a 2 p.m. screening of a short film documenting their story and the 2024 installation of a large mural honoring them.

Surviving family members will be on hand – including Chris Simkins, the son of Dr. Simkins, who’ll greet attendees and share memories of the men behind what has become a landmark Greensboro civil-rights case.

Gillespie will also commemorate the occasion by offering 75-cent green fees on Sunday – the same amount the Six paid in 1955 when they walked into the clubhouse, laid their coins on the counter, and asked to play a round just like any other taxpayer in the city. (Cart fees still apply, and anyone wanting to take advantage of the special rate can call the golf shop at 336-373-5850 for a tee time.)

On December 7, 1955, Gillespie Golf Course had already been operating for over a decade. It was built in 1941 under the federal Works Progress Administration; however, by the late 1940s the City of Greensboro had effectively turned it into a whites-only club by leasing it for a token fee to a private group.

That arrangement allowed the course to ban Black players, who were pushed instead to Nocho Park Golf Course – a far inferior alternative located next to a sewage plant. Conditions there were poor, and many African American golfers felt like they were being told, plainly, that their access to public recreation didn’t matter at all.

Dr. Simkins, a dentist and prominent civic leader, decided it did matter: He and the other five men went to Gillespie, paid their 75 cents, and – after being denied the right to sign the register – walked out to the first tee and hit their opening shots.

Accounts from the time describe the head pro confronting them on the course, yelling and threatening them with a golf club.

The men ignored the abuse and played nine holes before leaving peacefully.

That night, Greensboro police arrested all six on trespassing charges.

The men were convicted in early 1956 and were sentenced to 30 days in jail.

But they appealed, and, in 1957, a federal court struck down the city’s leasing scheme in Simkins v. City of Greensboro, ruling that the city couldn’t use a private-club arrangement to avoid constitutional obligations. A special three-judge federal panel affirmed the decision later that year, ordering the course desegregated.

Rather than comply, someone burned Gillespie’s clubhouse to the ground just days before the federal order took effect.

The city then condemned and closed the course – effectively sidestepping the court’s ruling. Gillespie stayed closed for years, and it wasn’t until December 7, 1962 – seven years to the day after the Six played their historic round of golf – that the course reopened.

Fittingly, Dr. Simkins struck the opening tee shot.

Though overshadowed nationally by the lunch-counter sit-ins that came later, the actions of the Greensboro Six were among the earliest direct-action civil-rights protests in the South. Their stand challenged segregation in public recreation nearly five years before the Woolworth’s sit-ins in downtown Greensboro made front-page news around the country.

Dr. Simkins himself went on to play a leading role in fights far beyond golf: he was a longtime NAACP leader and pushed for integration in hospitals, swimming pools, transportation and voting.

A 2024 mural, now familiar to players and passersby alike, depicts the Six and offers a permanent reminder of the day they chose to walk onto the course that tried to keep them out.

Sunday’s celebration is just the beginning: Parks and Recreation officials say the yearlong observance will highlight the full story of the Greensboro Six, the legal fight that followed and the impact their stand still has on Greensboro.