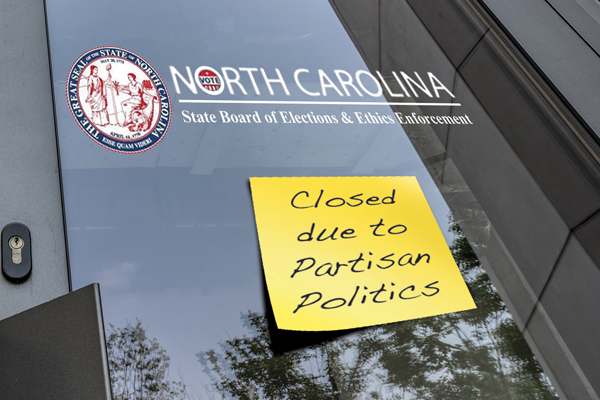

Those who follow politics know that North Carolina has been without a board of elections for nine months now, and they also know that absence is causing major problems. But what many don’t realize is that there’s another vital state board that’s likewise been in suspended animation since last July and remains that way today: the North Carolina state ethics commission.

Just like the state’s now defunct elections board, the ethics commission has been out of business due to a partisan battle now being fought out in both the legislature and the courts. Like the absence of an elections board, the absence of an ethics commission has meant that a lot of oversight at the state level isn’t getting done – and it may be costing taxpayers since that lack of oversight could result in leaders making decisions for their own financial gain.

The state ethics commission has been the body responsible for interpreting and administering the State Government Ethics Act. As part of those duties, the commission administers and oversees the financial disclosure process for individuals covered by that act, including state legislators, their employees and some of those that they appoint to various positions. The ethics commission also oversees judges, district attorneys and clerks of court across North Carolina.

A central function of the commission is investigating complaints of alleged unethical activity, such as decisions made where there’s a conflict of interest and state officials could benefit financially. The rulings by the board can have major implications for political leaders and taxpayers alike.

Last year, the North Carolina General Assembly merged the State Board of Elections with the State Ethics Commission into a new board named the Bipartisan State Board of Elections and Ethics Enforcement. Gov. Roy Cooper didn’t approve of the change and refused to appoint any new members to that board, which is why both boards are now on ice.

In January, the North Carolina Supreme Court struck down the General Assembly’s law that merged the board of elections and ethics commission in the proposed form. The General Assembly, attempting to address the court’s concerns, approved another structure for the combined board – adding a non-partisan seat among other changes. On Monday, March 6, a unanimous ruling by a three-judge North Carolina Superior Court panel preserved the new merged Bipartisan State Board of Elections and Ethics Enforcement; however, that decision may be appealed.

No one is sure how or when it will be resolved. In the meantime, the administrative staff of the two boards can perform certain functions but they don’t have the authority the two defunct boards possessed, and, therefore, staff is severely limited in what it can do.

The absence of a state elections board in a year of statewide elections has drawn most, if not all, of the media attention in the controversy; however, the nonexistence of a state ethics commission is also causing major problems.

Daniel Zeller, who served on the commission for two years until it was disbanded last summer, said the work of that board is extremely important, and he added that he has grave concerns about what’s not getting done.

“You’ve got to wonder what’s going on with ethics in the state,” he said.

Zeller added that, like the state’s elections board office in Raleigh, the ethics commission has staff that handles some tasks, but he said only the commission itself has the legal authority to determine whether actions by political leaders, judges and others are ethical or not.

“The commission acted more in a jurisprudence mode,” Zeller said. “They had to decide if there were any unethical actions. So you’ve got to wonder: Who’s making those decisions – or are they just stacking up?”

Zeller, a past chairman of the Rockingham County Republican Party who was appointed to the ethics commission by the General Assembly in May 2015, has worked in a family insurance business for much of his life and he now operates his own agencies in Reidsville and Eden. He said the commission hasn’t met since June of last year.

To take just one recent example of the type of case the ethics commission sees, last month, a conservative leader in Raleigh filed an ethics complaint against Gov. Cooper with the State Board of Elections and Ethics Enforcement, questioning whether Cooper violated state law by a permitting a pipeline to run through the eastern part of the state. The decision on that multimillion-dollar project could have huge implications, only there’s no commission to make the decision.

Zeller said most of the cases the commission has heard involved allegations of financial impropriety, and he added that politicians, their staffs and others may now have free rein to make decisions that benefit themselves, their friends and their families rather than the citizens they represent.

“The ethics commission deals largely with people using their authority to line their own pockets,” Zeller said. “The commission looked at complaints and determined, ‘Was it a breach of ethics?’ It was mostly about money.”

He added that the commission was kept very busy by that work, so there are no doubt a lot of government oversight functions that aren’t being carried out.

In addition to overseeing political leaders, the ethics commission, when it was operational, helped oversee the actions of judges, DA’s and others in the court system. Ethics of court officials is also overseen by the North Carolina Judicial Standards Commission, which was formed in 1973 to hear complaints about the actions of judges and other court workers.

Guilford County Chief District Court Judge Tom Jarrell said judges still have the Judicial Standards Commission in action to handle questions of unethical activity in the courts, but that body doesn’t oversee the state officials.

“We have the Judicial Standards Commission, but if the ethics board is not functioning then there is no one there to perform that oversight for the state legislators,” he said.

Jarrell said he and other judges across the state are required to file a Statement of Economic Interest – an “SEI” – for the ethics commission each year, which helps determine if judges have any conflict of interest in the cases they rule on.

Jarrell said judges must send in that form every year by April 15.

“The timing could not be worse,” he said, since it means judges might be filing income taxes and SEI forms at the same time.

Jarrell said those forms and their review by the ethics commission serve an important purpose.

“It’s a good thing – it helps us realize any potential conflicts,” Jarrell said.

He noted, for instance, that he used to own stock in Verizon and, at times, a search warrant pertaining to Verizon would come before him and he would rule on it.

“Truthfully, I hadn’t thought of that,” Jarrell said of the potential conflict.

He also said that, in the past, the ethics commission has done a very good job of working with judges on possible conflicts of interest that arise.

“They give us time to fix it,” he said.

The ethics commission – before it was merged with the state’s election board – consisted of eight members serving four-year terms. Four members were appointed by the governor and four others by the General Assembly with rules in place to assure that the board was bipartisan.

North Carolina General Statutes state that, other than some limited exceptions laid out in law, the ethics commission is the arbiter of these matters involving ethics in state government: “Except as otherwise provided in this Chapter, the Commission shall be the sole State agency with authority to determine compliance with or violations of this Chapter and to issue interpretations and advisory opinions under this Chapter. Decisions and advisory opinions by the Commission under this Chapter shall be binding on all other State agencies.”

The state’s elections board staff and ethics commission staff have already been merged into the same office area in a building in Raleigh, but of course, there are no board members to meet and handle either elections board questions or ethics commission questions.

Zeller said the merger of the two boards didn’t make any sense to him.

“To me, it was a great travesty to have been pushed in with the election board,” he said.

He added that he doesn’t see how a new combined board can effectively do the work of the two boards that both previously had their hands full.

“We were plenty busy enough,” Zeller said of the ethics commission he served on.

He also said that, while there are ethics decisions that apply to elections, the questions of financial malfeasance and other ethical issues that come up throughout government is much broader than the category of election law.

“There’s a whole set of laws that applies to elections,” he said. “The ethics laws apply to a broader category.”

Zeller said he doesn’t now what will happen to the previous ethics commission members. He had two years left on his own term.

“I’m in limbo,” Zeller said.

He said it’s been a great honor to serve on that commission that put a great deal of care into the process.

“The commission was truly bipartisan,” he said. “It did its work in a highly ethical, very moral, manner.”

Zeller said the ethics commission had some very impressive members with a solid grounding in ethics such as Clarence Newsome, who has a master of divinity degree and a doctor of philosophy degree from Duke University and was at one time president of Shaw University in Raleigh.

While the lack of a state ethics commission has a major effect on state players, it doesn’t affect the ethical oversight of local elected officials like the Guilford County Board of Commissioners.

Guilford County Attorney Mark Payne said that, when it comes to county commissioners and questions of their ethical behavior or financial dealings, the ones who make the call are “the voters and the courts and, to a smaller degree, the boards of commissioners.”

“There is a statute requiring all Boards of Commissioners to adopt a set of ethics; and receive ethical training; and there are a number of statutes setting out ethical requirements,” Payne wrote in an email. “There is no local government ethics board. The ethics board that was created as part of the State Government Ethics Act. In very few instances (and by ‘very’ I mean a few times every century) a Board of Commissioners can remove one of its own members through a common law procedure known as ‘amotion’.”

Payne added that in some cases a duty to investigate could fall on the county attorney.

“In practical terms, if the county received some communication that a commissioner violated an ethical standard, I suppose it would fall on me to investigate and determine what action, if any, was warranted, within the mandates of statute, Guilford County policy, the board’s code of ethics and the NC State Bar rules of professional conduct,” he wrote.