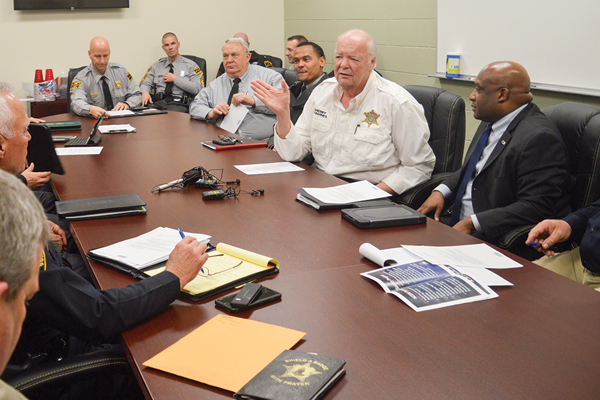

On Wednesday, March 21, by far the safest place in North Carolina to be was in the locked conference room inside the Guilford County Sheriff’s Special Operations Division building at 508 Industrial Ave. in Greensboro.

Packed tight into one small room were the sheriffs from central North Carolina counties, police chiefs from cities and towns in Guilford County, heads of security from local colleges, top brass from the North Carolina Highway Patrol and the SBI, and North Carolina Secretary of Public Safety Erik Hooks.

There was one reason and one reason only for the meeting in Guilford County’s most secure building – to find ways to keep the state’s students safe in schools.

At the March 21 meeting, the impressive collection of law enforcement officials held a tightly focused discussion about changes that could help make students safer from shooters and other threats. Some of the options discussed were providing wearable panic buttons to teachers, enhanced background checks of those buying guns, statewide use of security camera systems in schools, changes in school policies regarding the school systems’ interaction with law enforcement, and finding new ways to coordinate actions between multiple responding law enforcement agencies.

Hooks thanked Guilford County Sheriff BJ Barnes for setting up the meeting and said Barnes was one of the first people he reached out to in his attempt to find solutions. Hooks, who serves with Barnes on the North Carolina Governor’s Crime Commission, had asked Barnes to set up the meeting with the leadership of law enforcement in the region so state officials could hear their needs and also so the group could work together to find ways to mitigate school violence.

Hooks said he wanted to hear the best practices, concerns and successes of those in the room.

“I want us to constantly be in a state of evaluation at the state level,” he said, adding that he recognized a partnership with law enforcement was vital to addressing the problem. “We want to bring a unique and laser-like focus to this issue.”

The group did just that at the no-nonsense meeting. Unlike many meetings of government officials, the law enforcement officers and administrators cut to the chase and they were all business that afternoon. In fact, the meeting, which was scheduled for 2 p.m., started five minutes early – something unheard of when it comes to city council or county commissioner meetings. The discussion was devoted to actionable ideas that enhance school safety.

Barnes said he knew one thing that would help: the defeat of a proposed bill that would allow anyone who turned 18 to carry a concealed weapon provided they had no criminal record. Barnes said passing that law would make the situation worse at a time when solutions were needed instead.

“That’s just plain wrong,” Barnes said of the proposed change in state law. “There’s nothing magic about the age of 18,” Barnes said. “Just because you’re 18 and haven’t had a criminal record doesn’t mean you should be allowed to carry a gun concealed.”

Currently in North Carolina, the minimum age for concealed carry is 21 and the person must go through a concealed carry class and be certified to carry the weapon.

Barnes also said the National Instant Criminal Background Check System (NICS) – a 20-year-old system of checks mandated by the Brady Handgun Violence Prevention Act – simply isn’t working.

“NICS background check is a failed system and hopefully the government is going to fix that; supposedly they are going to,” Barnes said.

He added that local law enforcement officers know “who the bad people are and who should and shouldn’t have a gun” better than people evaluating forms in Raleigh. Barnes said that state and federal officials often don’t have all the facts or a good understanding of a person’s nature – as local law enforcement officers often do.

At the meeting, Barnes said another necessary move is convincing school officials of the need to provide information to law enforcement.

“A lot of the time, our schools are hiding information from us that we should know,” Barnes said. “They are not reporting a lot of crimes that we should know about. We’re going to end up pushing, I think, a little harder on the schools to not try to make it appear like everything is roses when it could very well be guns and roses.”

This has been a common complaint among law enforcement officials and, on the same day this high-powered meeting was taking place, a captain with the Guilford County Sheriff’s Department was giving a safety themed speech to teachers and making certain that they were aware of the things law enforcement officers need the school system to let them know.

One option discussed at the meeting was allowing armed volunteers in school if they had Basic Law Enforcement Training (BLET) certification. In 2013, the North Carolina General Assembly created the Volunteer School Safety Resource Officer Program in response to Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. Though the bill passed, the program hasn’t been established to any degree due to logistical issues and concerns about implementation.

At the March 21 meeting, Rockingham County Sheriff Sam Page said it made sense to use well trained and certified volunteers in schools. He said that it would allow former police and military officers to serve as a backup to school resource officers (SROs). The BLET program and certification is meant to develop the skills needed to become law enforcement officers. Page pointed out that in Maryland, a few days prior to the meeting, an SRO had confronted and shot a shooter, and, Page said, that demonstrated that trained individuals in schools could make a difference.

There seemed to be a consensus in the room that every school in the state now needs at least one armed SRO. Guilford County currently has SRO’s in all middle schools and high schools but not in elementary schools.

Another solution widely endorsed at the meeting was comprehensive video surveillance systems in all schools, with cameras that could provide live feeds to law enforcement. The Guilford County Sheriff’s Department is now pushing hard to get those cameras in Guilford County schools and some officers who spoke at the meeting said they wanted to see that type of system in every school in North Carolina.

Guilford County Sheriff’s Department Col. Randy Powers stated at the meeting that Guilford County offered the system to Guilford County Schools in 2010 but there was reluctance among school officials due to privacy concerns. Powers said times are different in 2018.

“I don’t think that’s going to be the atmosphere now,” Powers said.

Powers also said the camera system offers responding officers a huge advantage if there’s a shooter on a campus.

“We can see inside the school, and who he is and where he is,” Powers said. “So when we arrive on the scene we know who we’re looking for, what we’re looking for and where they’re at.”

Powers also spoke about a cell phone app now available that allows teachers to inconspicuously alert authorities when they see something of concern. It provides three buttons that alert the school’s front desk, law enforcement or medical responders. He said the same app allows a teacher or school administrator to use the phone’s camera to live-stream video to law enforcement.

Forsyth County Sheriff Bill Schatzman said some of the solutions require changing the way kids are being raised. He said the Forsyth County’s Sheriff’s Office started the SRO program years ago and that was one step toward addressing the problem of school shootings.

“But it’s going to take more than that,” he added.

Schatzman said society needs to take action to reduce violent tendencies in today’s youths. He said that would take the collaboration of teachers, parents and others.

“Young folks do not learn empathy,” Schatzman said. “What is empathy? What is respect? What is trust? Our entertainment today doesn’t support that.”

He said that everything from television to the video games on smart phones desensitize kids to violence.

“They don’t understand what the results of violence are,” he said.

Schatzman also said that school officials and others need to be much more aware of what to look for and, like Barnes, he said schools need to be better about sharing relevant information with law enforcement.

Schatzman has served on law enforcement teams that studied mass shooters.

“In every one of those instances we studied and talked about, the coworkers of the entity or the business say, ‘Yeah, I knew John was going to do that one day. I mean John was just a nut cake and he had guns, and blah, blah, blah.’”

At the March 21 meeting, North Carolina Division of Emergency Management Deputy Director Joe Wright said his wife is a teacher so he has a keen personal interest in school safety. He said his division had noticed early on that individual response agencies and schools were making a lot of excellent plans but they weren’t coordinated with one another. For instance, he said, one school had an evacuation area planned for the kids but that was also the place where the fire trucks expected to come rolling in.

“That’s a plan to fail,” Wright told the standing-room only crowd.

Wright also said the first responder on the scene may be a Highway Patrol officer who’s never worked with the SRO and only knows that officer by having coffee with him or her. He said all law enforcement officers responding to a call at a school need to have the same information, plans and training so they can act as a cohesive unit.

Wright also said his division is studying a wearable panic button for teachers, which would go on the lanyard for their nametag or somewhere else that’s easily accessible. One version has geo-tagging that allows law enforcement officers to know the location of the teacher. The geo-tag could also, he said, show the wearer’s elevation so responders would know what floor the teacher is on.

An SBI official at the meeting let the officer know that his department has a school threat analyst to help local state and federal authorities asses potential threats.

“We can help vet backgrounds and social media,” he said.

Arming teachers is one option for combating school shootings that some Guilford County commissioners and others are now proposing, but Gibsonville Police Chief Ron Parrish said he’s not in favor of that move. He said it would be better to have more trained and armed officers in schools.

“They may not have the mindset for it,” the Gibsonville chief said of teachers.

He said the communication between schools and law enforcement needed to be a lot better. He said that, earlier this year, a Gibsonville school had a school shooter drill which resulted in him and another officer responding to what they thought was a real shooter. He said that type of thing was very troublesome.

“There was no communication there,” he said.

A representative from the Highway Patrol at the meeting said his department is “a force multiplier,” there to assist local departments when needed.

Barnes said there needed to be an overhaul in the way Highway Patrol officers are dispatched when it comes to aiding local authorities. He said he hated to be “ the skunk in the room,” but he wanted to make the point that at times during responses to events, Highway Patrol cars are dispatched out of Raleigh rather than dispatched by local law enforcement officers, ones who know the situation and know where every patrol car is. Barnes added that sometimes life hangs in the balance and patching responses through Raleigh can reduce response times.

Federal Law allows honorably retired or active law enforcement to carry concealed in every state. North Carolina is a Mecca for retirees from many other states, especially Florida. I suggest that ANY retired police officer from ANY state who qualifies on the range and participates in a requisite course on school safety and more particularly specific schools in their areas, be allowed to VOLUNTEER as a School Safety Marshall. We have all had the same training, and law enforcement, public service and protecting others is in our blood, no matter where we were trained and certified. A one week course on NC law and school safety to become certified and deputized for this one purpose, is more than sufficient. It makes no sense to allow all of the millions of dollars spent training officers who are now retired and wish to be an asset to their community, to not be allowed to do so.

The Federal Law, HR-218 was put into effect, has had revisions and is there for a reason. Why not put it to good use and allow us to protect the children, our grandchildren and our future at no cost to any school district or county?

Asst. Chief, Ret.

certified CCH Instructor